Arriving in Crete in early November, the weather was surprisingly summery: well over twenty degrees Celsius, and the sea water was still surprisingly warm. Just like the Estonian pleasant summer! However, instead of enjoying this warmth, we had to spend time within the hospital walls.

We went swimming a lot with the kids and spent time at the beach. Suddenly, we noticed the longer Indy spent in the seawater and when she finally started to feel cold, her legs swelled even more, and the situation worsened. We assumed the opposite, that frolicking in the seawater would improve things.

As the situation seemed strange, we decided to find a pediatrician to consult with. It took several days before we found a pediatrician who spoke English. I even tried to make my way into the local Agios Nikolaos hospital with my broken leg, but this experience led us to seek a private doctor. There are many private clinics in Greece.

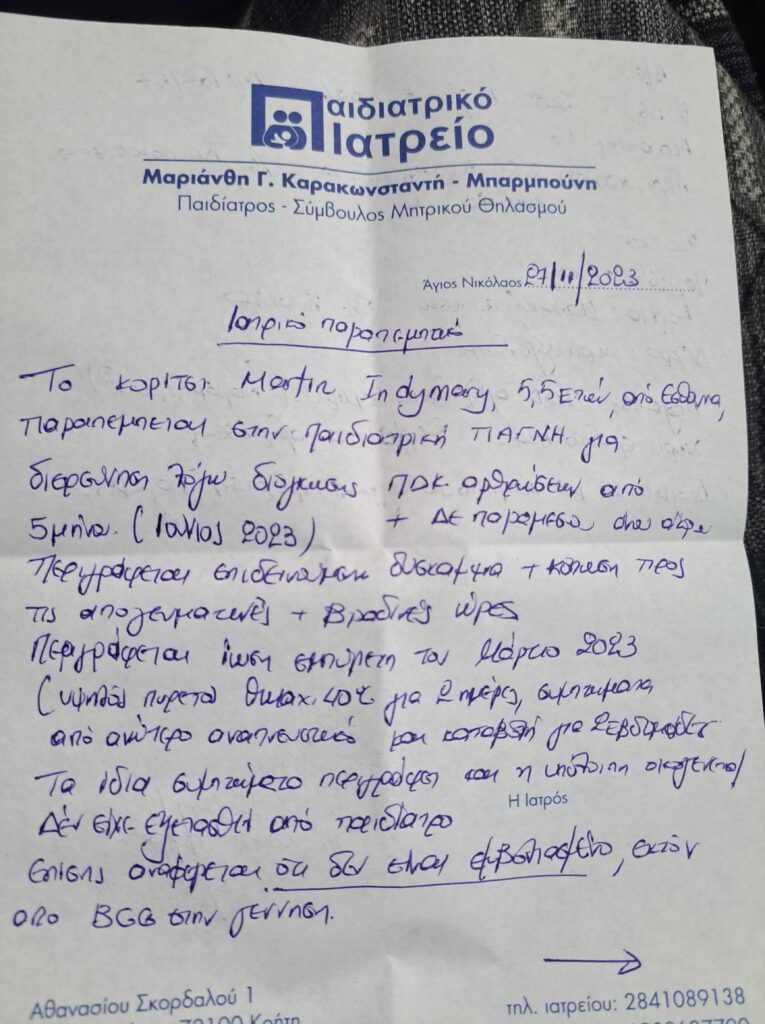

The pediatrician immediately issued a referral to the hospital.

As it can be challenging to handle things over the phone, as Greeks often hesitate to answer foreign numbers, we chose clinics from Google Maps and started going through them. Here, it’s common for work to be done from around 9 in the morning until the afternoon. Everything is closed during the day, and work resumes in the evening around 6. Entering one clinic in the morning, we got an appointment for Indy in just an hour.

The doctor took Indy’s concerns very seriously and examined her in detail. She listened to his heart for a long time and asked, “Do you know that your daughter has murmurs in her heart? ‘Tuk-tuk, tshh-tshh, tuk-tuk, tshh-tshh.’ ” To her, Indy’s situation seemed very strange and worrisome.

The doctor immediately started calling her acquaintances working at the medical university hospital on the island of Crete. “You should head to the hospital tonight,” she told us after the calls. I was taken aback. It was two in the afternoon, and I dismissed the idea because, accustomed to the work rhythms in Estonia, what would we possibly do in the hospital in the evening?

Nevertheless, we were expected at the hospital, and a very long referral was handwritten with a ballpoint pen. I had no clue what was written there.

If in Estonia, private doctor visits, in my experience, range from seventy to one hundred thirty euros. In the private clinic in Crete, the first visit cost forty euros, and each subsequent visit cost thirty euros.

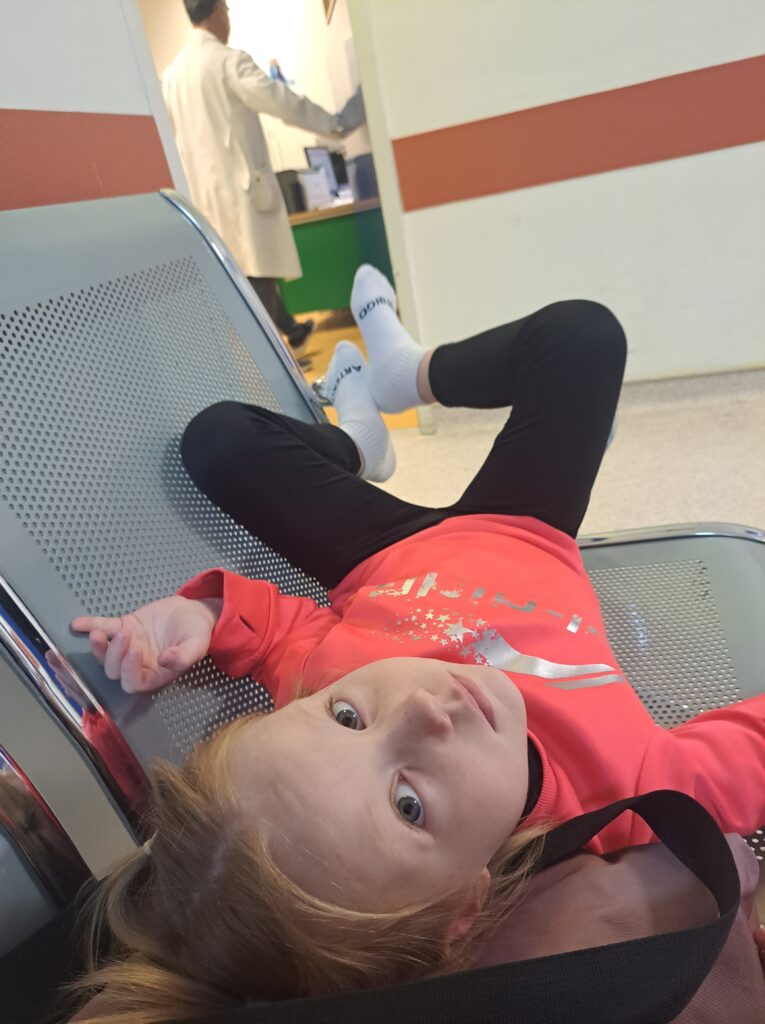

So, the next morning, we embarked on this journey. The hospital was a little over an hour away. In the hospital, we were directed to the emergency department, where we clearly waited for hours before getting in. The hospital nurse examined Indy, made more phone calls, and then a band was placed around the child’s arm, saying, “Now you have to stay in the hospital.” And I thought we were just coming here for a specific doctor’s appointment.

The news of staying in the hospital threw me off balance.

I was completely taken aback, and mentally, I had not prepared for this scenario at all. Additionally, I was still in an emergency cast and moving with crutches, which made the situation more complicated. The idea of being confined within the hospital walls in a foreign country, in a foreign language environment, triggered confusing and frightening feelings in me. At the same time, it seemed like a good opportunity to get to the bottom of Indy’s situation.

At times, I was afraid of what would happen next and what was currently so wrong that we needed to stay in the hospital. For them, the problem was serious and required investigation. I pleaded for the option to spend the day in the hospital and stay overnight in our own home, but that was not even considered.

As much as I have been in hospital walls in Estonia (fortunately very rarely: one tonsillectomy for me and having three children), it’s always an unpleasant environment. Once we had somewhat adapted to the hospital conditions in Crete, the environment here was something completely different. Fortunately, there was a large play area with many toys, and even outside, there was a playground to distract the child.

And let the procedures begin! Her height, weight, and the circumference of her legs were constantly measured to assess changes in swelling. Lymph nodes were examined, and joints all over the body were twisted and turned. Numerous blood and urine tests. We were attended to by various doctors constantly.

X-rays of the legs from multiple angles, as well as hands. Ultrasound. In the morning, Indy was woken up and told to step on the scale. Later, I realized that this was to check if there was morning stiffness in her joints. This whirlwind of activities lasted for three days, and in the end, I was extremely grateful for this experience because, finally, someone took the trouble to thoroughly examine our child, which was not done in Estonia.

The first day and evening were emotionally very difficult. Indy had never been away from her family like this, and on the first evening, there was a proper emotional breakdown. On the second day, when Tuljo came to visit us with other kids, Indy seemed like she wanted to hug them in half – she was so happy! As we got the hang of the system, we could leave the department for a while to replenish supplies, breathe outside the hospital walls, and clear our heads.

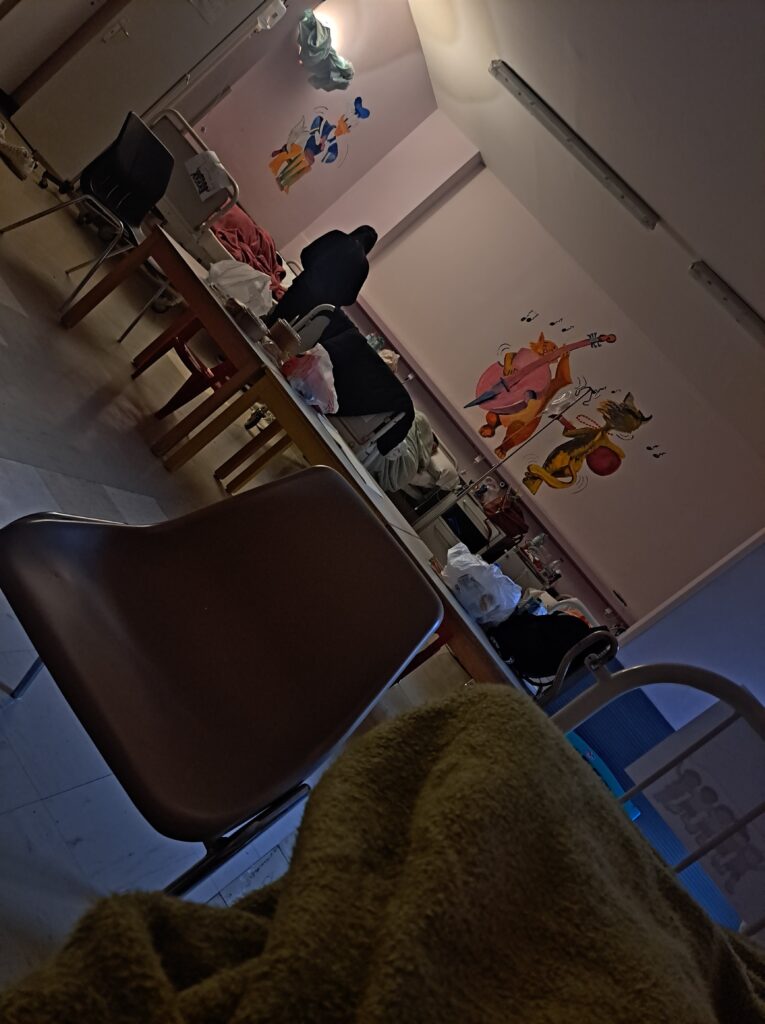

Together in a small iron-barred bed

The furnishings in the Greek hospital were relatively outdated. The toilet didn’t even have a seat. Overall hygiene left much to be desired. Directly from the ward, you could step outside to smoke. There were a total of five patients in our ward. According to the rules, only one parent can be with a patient, and visitors are not encouraged. Greeks, in their typical fashion, disregard such rules. Greek families flowed in and out of the hospital. Grandparents, uncles, aunts, and siblings, all continuously came and spent their days with the patient. It was a crazy crowd constantly passing through the ward. In Estonia, it would be unimaginable for people to walk in with outdoor shoes and outerwear, but here life just goes differently, and it was fascinating to observe.

Five patients and five iron beds. In the evening, I asked the older sister of my roommate where the parents do sleep here. She smiled and said that mothers and fathers sleep on chairs. We didn’t even have a blanket on the bed. Fortunately, we managed to get a blanket and a pillow from one of the nurses.

At nightfall, when the lights went out, I just crawled into that tiny iron bed next to Indy and tried to somehow endure the night. The solitary experience without the family was emotionally quite tough, but all for the sake of finally addressing and investigating our child’s condition. How long we had waited and wished for this!

The X-ray revealed no bone changes. In the ultrasound, we saw that there was too much fluid around the tendons and between the joints as if the fluid had aged. Every day, the department’s professor, along with all the department doctors, visited each patient to discuss the situation. All doctors brainstorm and try to find solutions; one explains to others what ails the child, and everyone puts their heads together and brainstorms. In our case, they bet that it might be some bacterial gas causing this situation.

As I understood, no doctor here decides things on their own; multiple heads are always better than one. In addition, your pediatrician changes every month. Perhaps to bring in fresh ideas and a new approach? In addition to the pediatrician, we were also attended to by a rheumatologist and an orthopedist.

They thought that it might still be Lyme disease and took a test just in case. Without waiting for the results, we were finally sent home, but the head of the department, the professor, asked us to start an antibiotic course. As you already know, antibiotics brought a significant change for us, but unfortunately, we were asked to stop the course as they had no reason to continue, since the Lyme disease result was negative.

By now, we have had two Lyme disease tests done because, according to the Greeks, anything can happen in the lab, and repeat tests are always necessary.

Upon leaving the hospital, we were given a referral for a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Since the queues at the public hospital were very long, we chose the path of going to a private clinic to get it done faster. We attempted to do the MRI without anesthesia. The sounds and the confined space eventually got Indy so worked up that the process was quite challenging. After one leg was done, we had to take a break and calm down for an hour. Fortunately, the clinic staff was understanding, and we were able to continue afterward. It revealed excess fluid in the tendons and joints, thickening of the joint fluid membrane, swollen bone marrow, and a one-centimeter cyst below the ankle.

No solutions yet

In short, the situation is complicated, and even the department’s professor privately told me to reserve time and patience because solving this issue is not at all straightforward. Meanwhile, please send all your positive thoughts and wishes our way so that our little Indy Mari can run with all her strength again, as typical for a child, and enjoy life to the fullest. So what I was told in Tallinn, that she won’t end up in a wheelchair but also won’t become an athlete, doesn’t come true. Believe it or not, Indy is deliberately aiming for very strong athletic achievements.

In summary, the stay in the hospital in Crete was not overly oppressive – play areas and playgrounds significantly eased the situation, and when we finally got used to the local way of life and occasionally slipped out of the department, the situation didn’t seem so bleak. Once the initial shock of the first day had passed, we viewed the situation from a more positive perspective the next morning. But yes, for anyone ending up in a Greek hospital, bring your own blanket and pillow, enough food and drink. Due to a shortage of nurses, families take care of their own in the hospitals.